In this week’s blog post, SGSAH student Kiah Endelman Music tells us about a somewhat unexpected find in GSA’s institutional ephemera collection…

Whilst sifting through a folder comprised largely of student postcards and exhibition catalogues, I came across an unexpected item – an envelope of material relating to the Newbery family that had somehow made its way from the Mackintosh library into the archive’s published ephemera collection (GSAA/EPH/12). This envelope revealed several gems, from floral watercolours and Christmas cards designed by Mary Newbery Sturrock to a comical caricature of Francis Henry Newbery, to an article written by him in 1901 discussing art education in Scotland and at The Glasgow School of Art specifically.

Among these papers nestled the most unexpected and amusing find – three type-written copies of a song titled ‘Dumble-Dum-Dearie. Or How Fra Newbery Got His Cloak And Hat. The School Of Art Song.’

GSAA/DIR/5/38: ‘Dumble-Dum-Dearie or How Fra Newbery Got His Cloak and Hat; The School of Art Song’, unauthored [1916].

Despite this title, no one working in the archive had come across or heard about the song before!

Though undated, the lyrics detail the many goings on at GSA during Francis Newbery’s tenure as Headmaster and Director between 1885 and 1918, jauntily commenting on and celebrating his contribution to life at the school, his commitment to its staff and students and, perhaps more surprisingly, his distinctive style of dress.

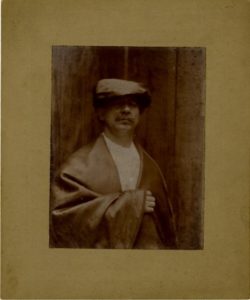

Both the song’s title and its concluding lines refer to Newbery’s characteristic ‘cloak and hat’, painting a picture of his bold and memorable appearance. Peter Wylie Davidson, a sculptor and silversmith who both studied and worked under Newbery at GSA, describes how his ‘dignified and well-groomed figure became noticeable in the town. Even men in the street would ask, “Who is he?” as he wore a unique tall black hat and frock coat of the period.’[1] Newbery’s notable fashion seems to have contributed to his impression upon acquaintances as a ‘man of address’[2], though the authors of ‘How Fra Newbery Got His Cloak and Hat’ approach his attire in a more tongue-in-cheek manner, suggesting in the song’s conclusion that Newbery’s garb in fact belonged to GSA and that, as ‘Fra took his leave’, he ‘borrowed his cloak and purloined his hat’ from the school itself!

These final lines bid goodbye to Newbery, suggesting that the song was likely written and possibly performed by students to commemorate Newbery’s early retirement in 1918.

GSAA/DIR/5/38/7/2: Photograph of Francis Newbery, head and torso, wearing large beret style hat and draped with cloak around shoulders, c1903.

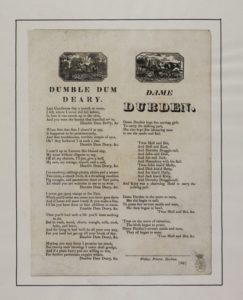

The song comprises thirteen verses, each four lines accompanied by a refrain of “Dumble-dum-dearie-cum-dumble-dum-day”. Some quick research revealed that this refrain and the song’s tune are based on the similarly titled ‘Dumble Dum Deary’, a popular ballad printed on numerous broadsides in the 1800s in England also known as ‘Richard of Taunton Dean’.

Widespread between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, broadside ballads tended to focus on urban and daily concerns, on love, legend, drinking-songs and religion. As in the case of ‘How Fra Newbery got his Cloak and Hat’, the name of a known tune would often be printed above the ballad’s title, followed by the lyrics, written to match.

One example of a broadside featuring Dumble Dum Deary (c1830) is held by the National Library of Scotland and can be accessed here.

Dumble Dum Deary, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

Accompanying the refrain, the song’s lyrics describe the many feats Newbery achieved during his 33 years in post. Newbery played a huge role in the development of the Glasgow School of Art, its curriculum and international reputation. The song details, for example, the erection of the Mackintosh building, the creation of the new Diploma course and the broadening of the student body, ‘full with Painters and Sculptors and Arkeytects/ Of various ages and every sex.’

The song also discusses Newbery’s support of the school’s students both pragmatically, via the ‘Fifty-Pound Travelling Scholarship’ (worth £2,291.73 in 2023) and the ‘Maintenance Bursary’, as well as artistically, via the introduction of a lecture scheme featuring renowned artists and designers such as Walter Crane, William Morris and James Whistler McNeill, and via the time Newbery spent collecting numerous plaster casts from across Europe to aid the students’ study.

GSAA/P/1/23: Photograph of Newbery and others looking at casts in the Mackintosh Building basement c1900

Many verses of the song are dedicated to professors appointed during Newbery’s tenure, each one’s personality and teaching style both honoured and made light of. Among those mentioned are Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Eugene Bourdon, Maurice Greiffenhagen, Georges-Marie Baltus, James Dunlop and Robert Anning Bell. Baltus, Belgian painter and lecturer, is portrayed as ‘the tempera toff’, equally skilled at painting and drinking dry gin. Maurice ‘Greiff’ Greiffenhagen, whilst unparalleled in his knowledge of life study, ‘never spoilt no one by sparing the rod’. And James Dunlop, deputy head of GSA from 1886 is described as the ‘the anatomy bloke’, who sat ‘on his “gluteus”’ to teach and appears to have had a formal preference for the ‘external oblique’.

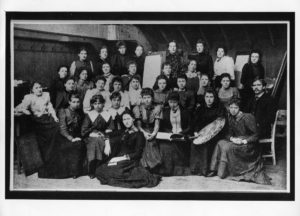

Surprisingly (or perhaps unsurprisingly!) the song does not mention any of the achievements or appointments of women at GSA across the period of Newbery’s Directorship, of which there were many! Much of Newbery’s success was due to the acclaim and notoriety surrounding the designers and artists of the 1890s who worked in The Glasgow Style, including ‘Glasgow Girls’ and GSA staff and students, Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, Frances Macdonald MacNair, Jessie M. King, Ann Macbeth and Newbery’s own wife, Jessie Wylie Newbery. As Jude Burkhauser writes, Newbery’s ‘enlightened direction provided equal encouragement to male and female students’[3] and his directorship saw a period of time where women were actively pursuing careers in art and design, and an environment in which women were able to flourish as both students and teachers.

Perhaps these omissions provide an indication that the song was written by the male students of the day!

GSAA/P/1/5: Photograph of women students with Francis Newbery, 1890-1891

Despite its gaps, the song gives a fascinating insight into an experience of GSA in the early 1900s, far more casual and humorous than can be found in most official records! I was very glad to come across ‘Dumble-Dum-Dearie’ and have truly enjoyed my time spent deciphering the histories and meanings of the lyrics, amused by the various quips directed at various staff and appreciating the deep respect students had for Newbery’s time and work at GSA.

The song and the rest of the material found in the envelope has now been catalogued and can be found here, within Francis Newbery’s papers (GSAA/DIR/5/38).

Please see the second blog here accompanying this post for a full transcript of the lyrics.

[1] Davidson Family Collection, Peter Wylie Davidson (Unpublished autobiography), pp.44-51.

[2] John Sparkes GSAA, Newbery, Testimonials, (1885), p.3.

[3] Jude Burkhauser, Glasgow Girls: Women In Art and Design 1880-1920, p.20