Design

From 1845, as a Government School of Design, The Glasgow School of Art followed the South Kensington system, which provided a national curriculum in art and design practice intended to advance production and manufacturing of styles, techniques and quality of British goods at the height of the country’s imperial ambitions (Olalquiaga, 1999).

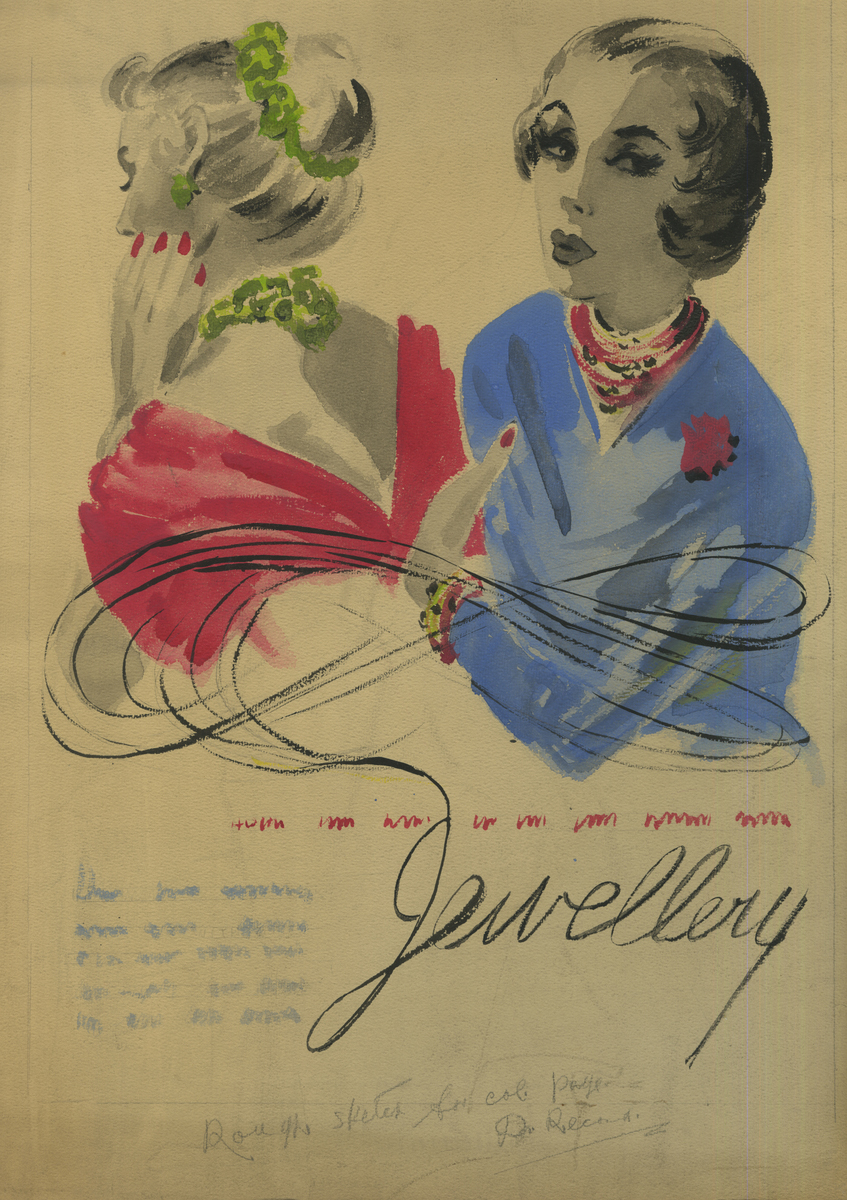

Since 1845, ‘Design’ as a distinctive school or department at The Glasgow School of Art has been in existence, and aspects of the original aims of the government school are reflected in the continued teaching of specific design subject areas: Textiles (and Fashion), Silversmithing & Jewellery, Communications Design, Product Design Engineering, and Interior Design.

GSA’s Archives and Collections include design work ranging from pre-1889 to the present day, made by students and staff, or collected as part of teaching and instruction, such as the School’s collection of plaster casts of sculptures from antiquity, for example.

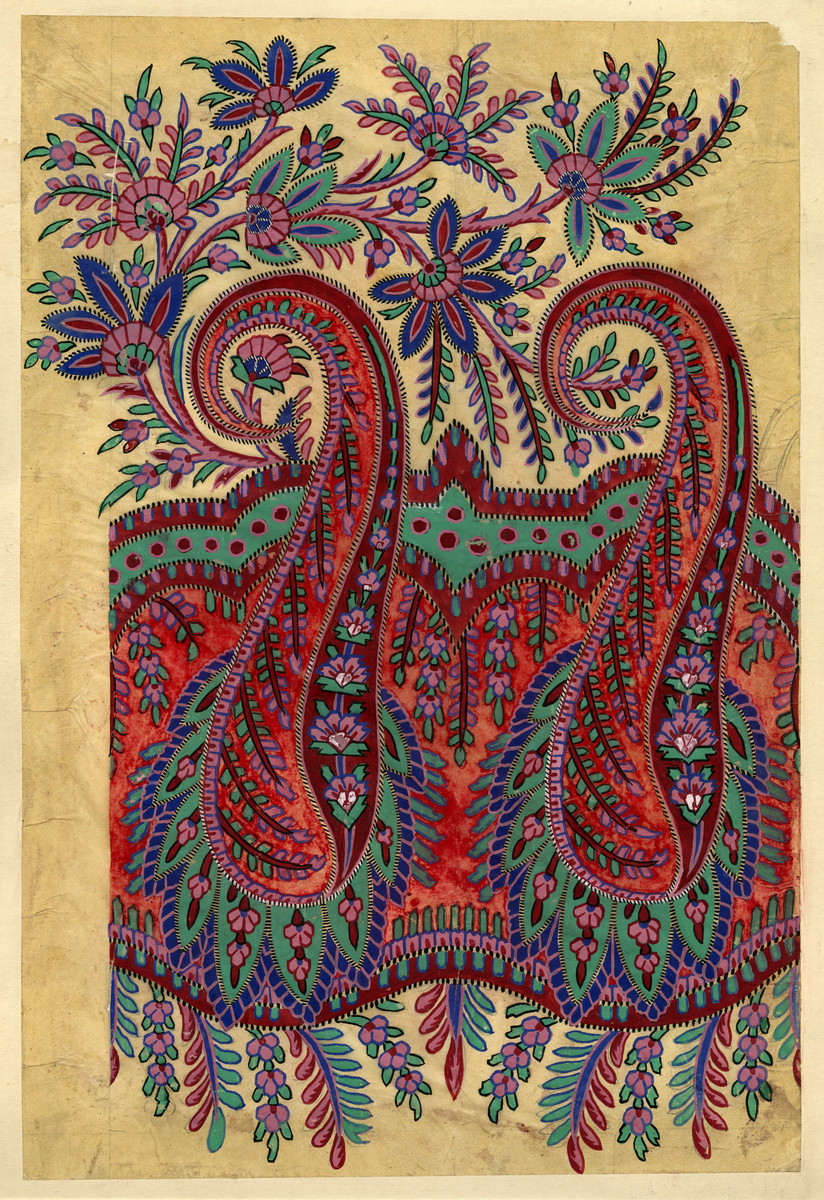

The scope of design work in the Archives and Collections is rich and comprehensive, it exemplifies the best of the School of Design’s performances in the past and in recent times, and it is striking how such productions vary from simple textiles and embroidery to prestigious pieces of silversmithing and jewellery.

Browsing through the digital archives, you quickly discover a recent addition to the collections, Jonathan Boyd’s beautiful Glasgow Commonwealth Games Medal, 2014, a now ‘legendary’ commission. Designed, made and distributed from the School of Design’s Silversmithing & Jewellery department, the designer and S&J colleagues worked tirelessly over the period prior to the games to meet their commitment of creating fine-quality, hand-crafted, objects, following in GSA’s long tradition of medal design.

Not surprisingly, decorative arts make up a significant proportion of the collections at GSA overall, as much of the School’s early history is dominated by ‘applied arts’, many of which created and made by women. One example is a ‘Mantel Clock’ by the designer De Courcy Lewthwaite Dewar (1878-1959), who, quite incredibly, taught metalwork at the School for thirty-eight years. The Mantel Clock is not quite as important or as rare as some of the more priceless objects in the collection, its meanings are apparent in the experimental nature of its design and execution; made by a young woman taking up the challenges of the arts and crafts movement, producing eastern European, folk-inspired craftwork at a time when Glasgow’s middling sorts were pursuing a rather more sophisticated style in Beaux-Arts and Art Nouveau productions.

Nor is it a surprise to find in the Archives and Collections a predominance of Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928) works. An architect and designer, Mackintosh’s output is now, also, legendary. Among those Mackintosh pieces that survive (some of which now exist only in digital form) is the rather squat and ‘dumpy’ ‘Barrel Chair’, designed for the city’s Ingram Street Tea Rooms, c.1907. The features of this design are so simple, spare and ‘un-decorated’ that it’s feasible that Mackintosh already had in mind Adolf Loos’ ‘Ornament and Crime’ as the ‘design brief’ of Ingram Street’s interiors. For all its modesty, however, the Barrel Chair might be considered a precedent for its chunkier Modernist child, Eileen Gray’s Bibendum Chair (1926), which afforded its sitter a slightly more comfortable, if marshmallow-like, plushness.

Mackintosh is sometimes associated with a form of Glasgow asceticism, however, he and his associates, his wife Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, her sister, Frances Macdonald MacNair, and Frances’s husband, Herbert MacNair, were turn-of-the-century aesthetes, always flamboyantly dressed in a full complement of dandified costumes and apparel, including velvet cloaks and excessive neckties. Their unconventionality in dress and manners is typical of art students then as now.

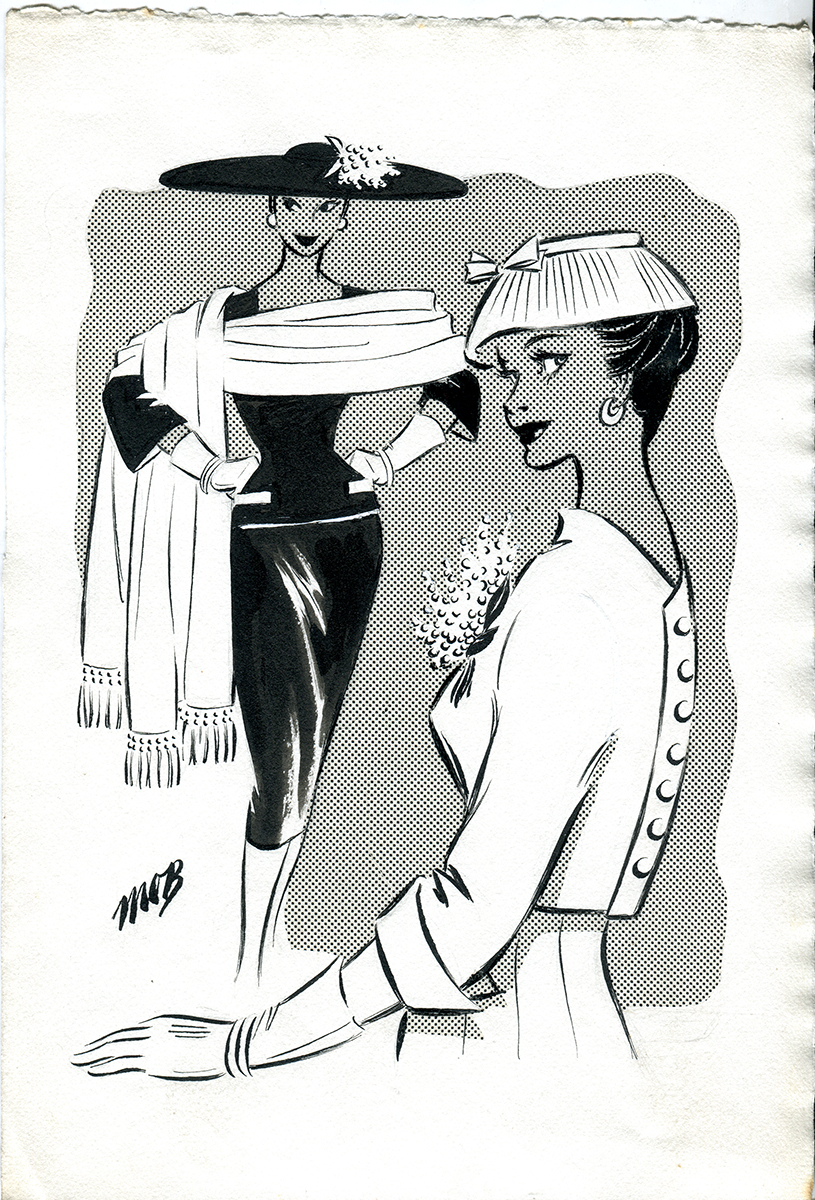

In GSA’s collections is a series of short film clips of student fashion shows from the 1970s-1980s. These provide a glimpse into counter-cultural trends of the period, including New Romantics, Punks and Goths. The styling of the films and their content are reminiscent of fashion shows at London’s Central St Martin’s immediately after that David Bowie video for Ashes to Ashes (1980).

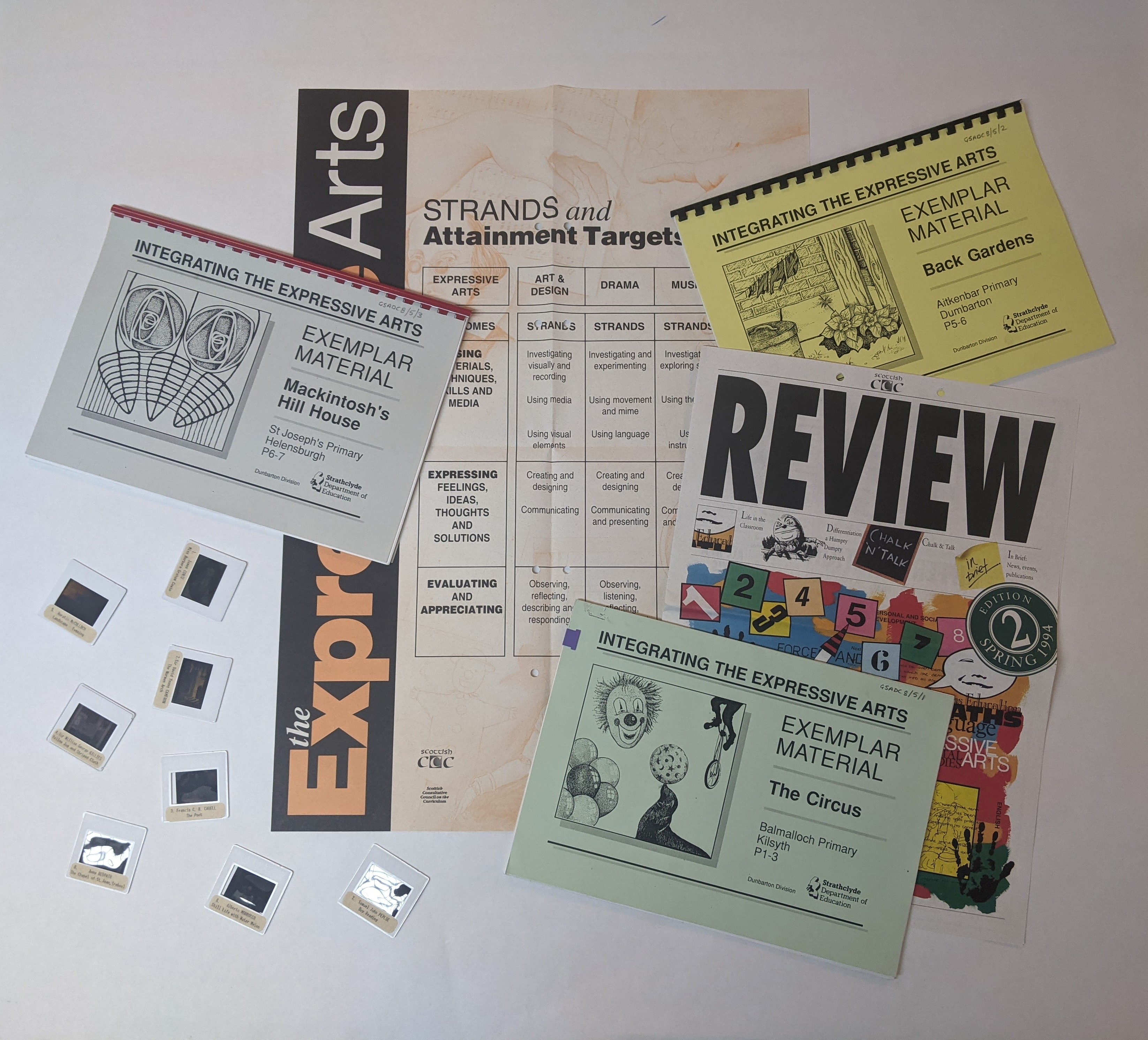

Closely related practices, fashion and textiles design feature prominently in the School of Design’s archives and collections, particularly historical textiles. This was the subject of a recent design research exhibition at GSA, Interwoven Connections, curated by Dr Helena Britt, who worked on the Stoddard Templeton collection of carpet designs. The unique ‘design library’ of this prominent and hugely successful Glasgow-based company is now incorporated in GSA Library’s special collections and offers a rich resource of period design styles for textiles.

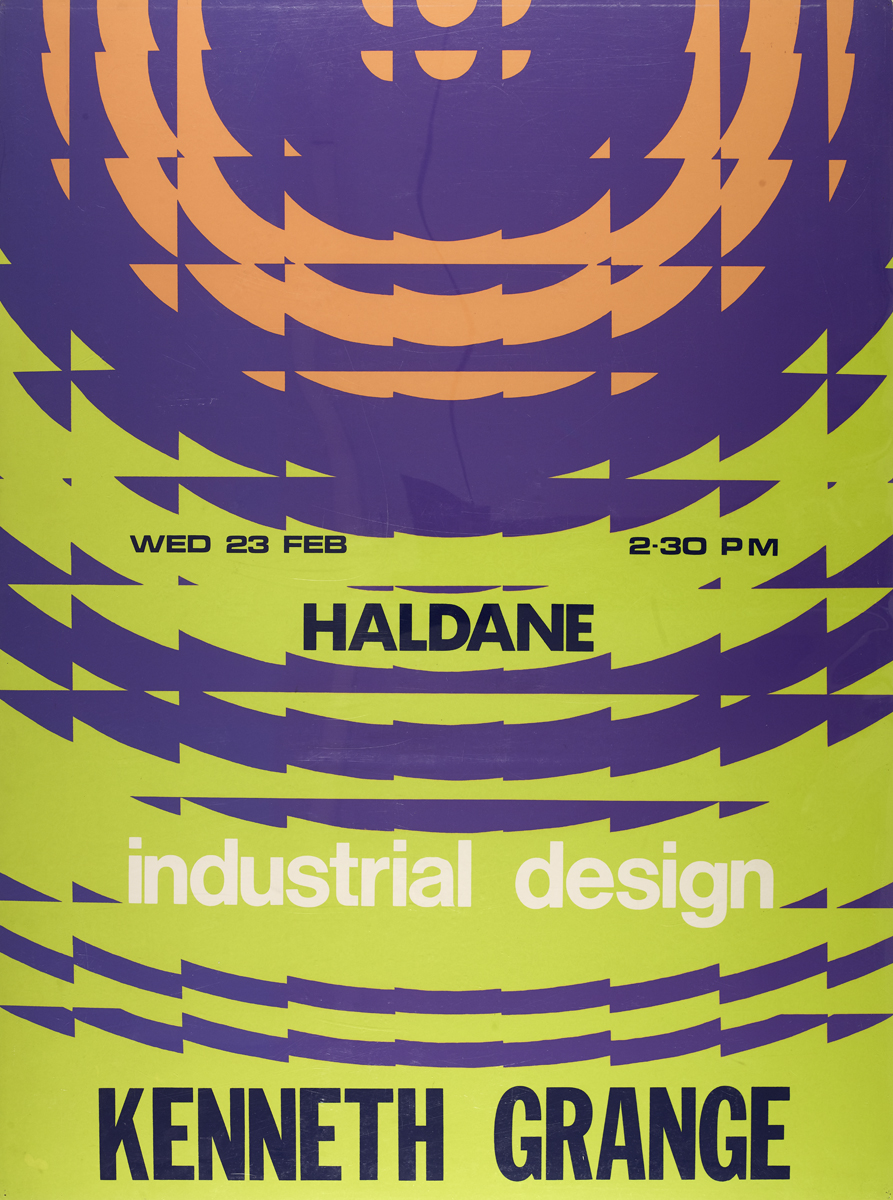

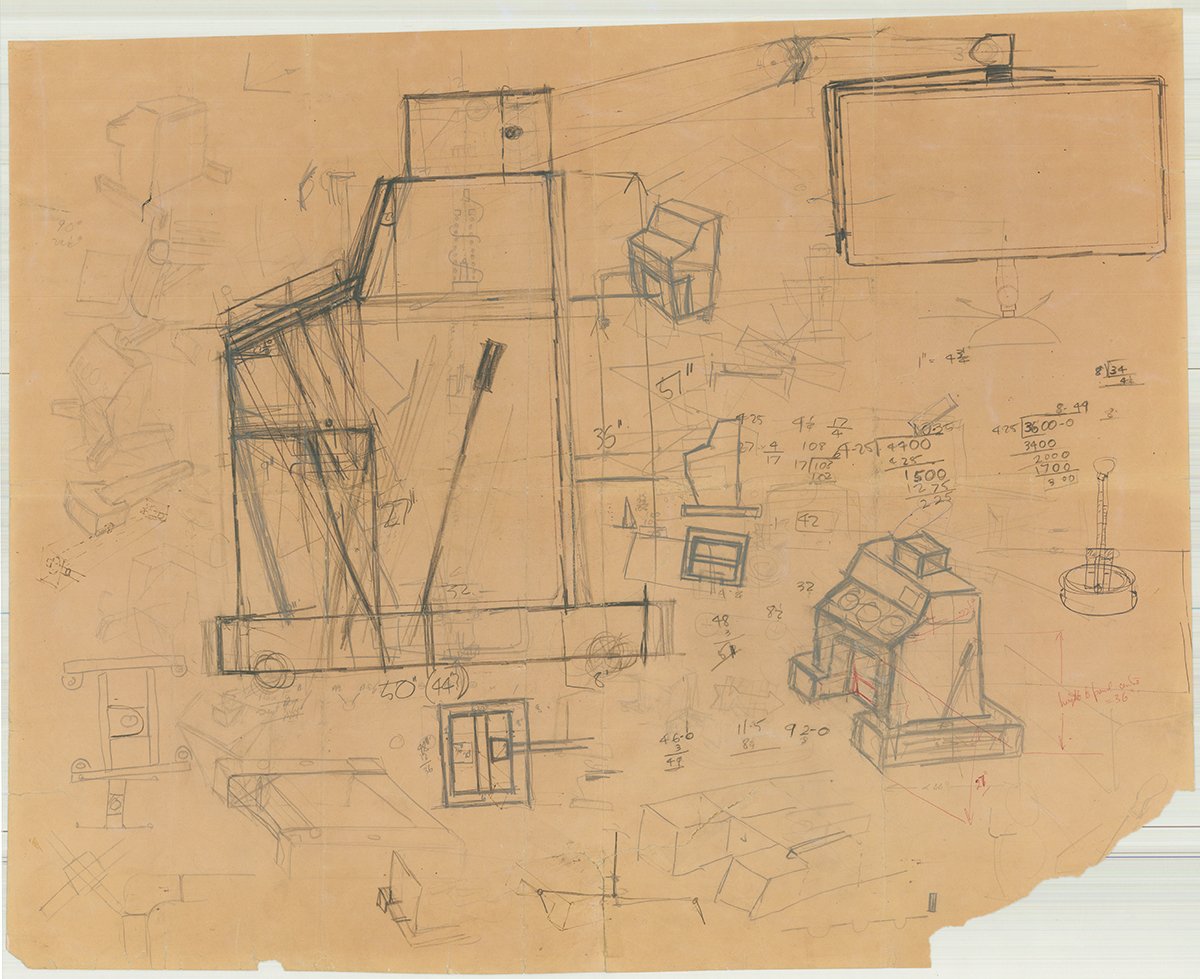

Another recent design research project based on the School’s Archives and Collections, is Professor Alastair Macdonald’s exhibition, Ultrasonic Glasgow, that focused on the pioneering designs of Dugald Cameron, an artist and industrial designer, who was Director of GSA from 1991-1999. Macdonald consulted material relating to Cameron’s work, early drawings, plans and sketches, to demonstrate his individual contribution to the advancement of ultrasonic equipment in medical use, particularly in obstetrics.

Design practice in the School of Design is leading on many of aspects of digital technologies, particularly in the fields of digital crafts, smart fabrics (Centre for Advanced Textiles CAD), and digital printing. How these new forms of design will be catalogued is yet to be discovered. Perhaps digital reconstructions of the Mackintosh building itself will prove to be the testing ground for these exciting new possibilities.

When William Morris (1834-1896), the arts and crafts designer, poet and visionary, planned his lecture to students at The Glasgow School of Art in 1889, on ‘The Society of the Future’, he was contemplating the new century and the chance to re-assess human labour, what it cost and how it was exploited in his own day. These issues of human and more-than-human costs to life in the twenty-first century are concerns for today’s designers.

Unlike Morris, however, designers in the present are not suspicious of technology, instead, they are embracing change and adapting technologies to sustain and improve life on the planet, because designers are, after all, essentially optimists (Dunne & Raby, 2013), as is clear by the many examples of their work preserved in GSA’s Design Archives and Collections.

Sources

- Jude Burkhauser (1988): Glasgow Girls: Women in Art and Design, 1880-1920, Canongate Books, Edinburgh

- Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby (2013): Speculative Everything, Design, Fiction and Social Dreaming, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Brian Dillon (2013): 'Eileen Gray', exhibition review in London Review of Books

- GSA Exhibition (2013 - 2014): Interwoven Connections

- Adolf Loos (1931): Ornament and Crime, Penguin Classics, London

- William Morris (1890): News from Nowhere, Cambridge University Press

- The Guardian (2020): 10 of the world's best virtual museum and art gallery tours

- Celeste Olalquiaga (1998): The Artificial Kingdom: A Treasury of the Kitsch Experience, Bloomsbury, New York and London

- GSA Exhibition (2019): Ultrasonic Glasgow: A celebration of The Glasgow School of Art's contribution to the history and development of medical obstetrics ultrasound