In Part One of Archive Gaydar, Archives and Collections Assistant and Researcher Helen Victoria Murray shared tips for LGBT+ research in the archive. For Part Two, she uses a case study from her own research as an example of how to put ‘queer possibility’ into practice.

In my previous blog, I wrote about moments in the archive where your gaydar pings, and how you can pursue these instincts through research. Let me introduce you to two women who pinged my gaydar: Ella Reid and Bunty Cairns. These women’s histories intertwine through GSA’s institutional archive, revealing social histories and queer possibilities.

Personal Histories in Institutional Archives

I first meet Ella Alexander Reid while researching in GSA’s Institutional Photographic Collection. I’m searching for a photograph of a woman named Margaret (Peggy) Morrison, who would later become an actress and author under the name March Cost. In the photograph, Cost, wearing a theatrical, orientalist costume, looks to camera with a confident, sensual gaze. The photograph is inscribed, ‘To Ella, with all my love.’ The charged image and caption intrigue me – who is Ella?

Margaret Morrison Front and Back GSAA_P_0001_1229 v1/v2

Making my way through the pictures, Ella repeatedly features. She’s small in stature, with a direct, confident gaze and mischievous expression. She is often photographed wearing ties, kilts and boxy masculine tailoring. She frequently has a cigarette in hand. My archive gaydar pings again: Ella’s self-styling reminds me of similar fashions worn by lesbians from the 1910s-1920s, such as Radclyffe Hall, the author of revelatory lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness.

Ella, GSAA_P_0001_1109

Ella, GSAA_P_0001_1143

The photographs centre around the social circle of two women: Ella Alexander Reid and Jessie Mary Cairns, nicknamed Bunty. Both women’s student records have been captured in biographies as part of GSA’s Home Front Memorial project, which researched all of the students at GSA during WWI. Ella Reid was enrolled at the GSA for a long stretch of time, from 1908-1919, and Bunty Cairns from 1915-1920.

Photograph of Ella Reid and Bunty Cairns in the studio GSAA_P_0001_1125

This series of photographs were added into the collection around the year 2000. Cataloguing methods change over time. Nowadays we would likely catalogue these photographs as a separate collection, but at the time the photographs were amalgamated with institutional photographs. Having moved from a private collection to an institutional one, they feature inscriptions, names, dates, messages and commentary that are more personal.

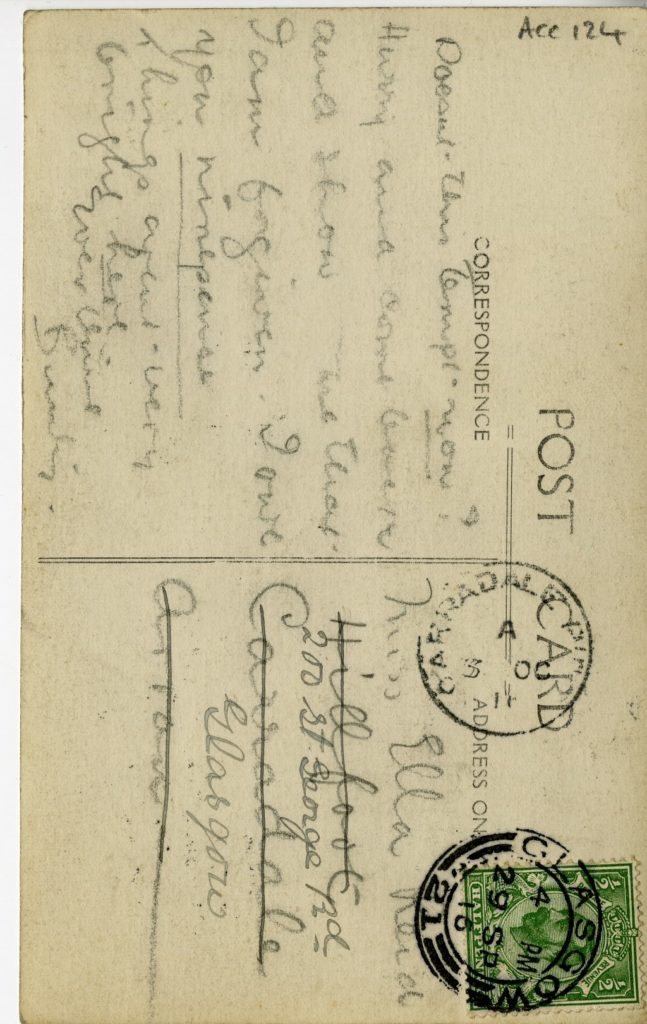

It’s unique to find so much personal material in this context. I become even more intrigued when I find a postcard photograph of the Mackintosh building, addressed from Bunty to Ella. It reads:

Doesn’t this tempt you? Hurry and come back and show me that I am forgiven. I owe you ninepence. Things aren’t very bright here. Ever thine, Bunty.

Postcard text image – GSAA_P_0001_1157 v2

The tone of this letter suggests the women’s closeness. Allusions to temptation and forgiveness have distinctly romantic connotations. I also want to call attention to Bunty’s sign-off, ‘Ever thine.’

In an otherwise casually written message, ‘ever thine’ stands out. I suspect Bunty is making a reference. ‘Ever Thine’ is a truncated version of a sign-off in Ludwig Van Beethoven’s Immortal Beloved Letter. The full phrase is ‘Ever thine, ever mine, ever ours.’ This letter is widely considered to be among history’s most romantic letters. The letter was published in 1840, and had been in circulation for decades prior to Bunty’s postcard; it is possible she could have read it. If the reference to Immortal Beloved was intentional, this is particularly poignant. Beethoven never sent his letter, and its intended recipient remains unknown. This kind of mystery and secrecy resonates with the experience of researching queer possibility.

Another intriguing hint at Ella and Bunty’s shared history appears in a photograph of a student group that has been intentionally cut up. When I first saw this image, all we knew was that someone had cut it. Then I made a discovery: elsewhere in GSA Archives, The Papers of Archibald Haswell Miller features a complete version of the same photograph. When I layer one image over the other, whose face has been removed? Bunty Cairns.

Cut image of student group, GSAA_P_0001_1149

Bunty Cairns cut out DC98_1_4_2_30, layered with image of student group GSAA_P_1_1149

What are some reasons to remove a face from a photograph? It might be for negative reasons, such as erasing unpleasant memories, or sentimental reasons such as putting them into a locket or keepsake. We don’t know who removed Bunty from the photograph or why, but the fact she was removed suggests intriguing private histories.

Bunty Cairns’ career at GSA was not all sunshine. In one letter to the Secretary and Treasurer in 1918, she writes:

I am very sorry to have to tell you that it is impossible for me to attend classes at school this winter. I have had rather a severe illness during the holiday and have been ordered to spend the winter in the country.

(GSAA/SEC/1 – 1918, Folder ‘C’).

More sadness follows in 1919, when Bunty writes again:

I very much regret to tell you that I cannot attend school this session. My mother died last week and I must stay at home this winter.

(GSAA/SEC/1 – 1919, Folder ‘C’).

Despite Bunty’s intentions to return for teacher training and take up an appointment as GSA’s wardrobe mistress, life intervened. After her own illness and her mother’s death, Bunty misses a year, re-enrolling in 1920. I have not yet been able to trace what she did next in her career, other than a mention in The Scotsman in 1920, revealing that prominent GSA alumna Dorothy Carleton Smyth exhibited a portrait at the Art Club of “Miss Bunty Cairns.”

Bunty alone with sculpture GSAA_P_0001_1051

We know from marriage records that Bunty Cairns went on to marry and have children with Angus Drummond in 1923. I mention this because it is common to dismiss any possibility that a historic person is queer once we know about their heterosexual relationships. As a bisexual woman, this topic resonates with me – biphobia often intersects with patriarchy. People assume a bisexual woman is purely straight, or a bisexual man purely gay, since attraction to men is culturally prioritised. On the other hand, as historians, we must tread a careful line. I am curious about my subjects’ potential queerness, but I do not want to define them or speak for them.

So what do we know? The photographs show that Ella and Bunty were close. They are photographed touching and embracing; they write intimate messages. Later photographs in the sequence date to 1938, nearly 20 years after both women finished their studies at GSA. We can infer from this that the women kept in touch. Someone outwith GSA has carefully kept these photographs before donating them, and captioned all of them with Ella and Bunty’s names, implying that their shared history was important to the owner.

Ella and Bunty in conversation, GSAA_P_0001_1121

Ella and Bunty laughing and smoking cigarettes, GSAA_P_0001_1224

Whether romantic or platonic, the friendship of Ella Reid and Bunty Cairns is a fascinating window into the social life of GSA students during WWI. But there are more questions about Ella Reid’s identity, and more hints of her queerness. In Part 3 of this series, I will introduce you to Reah Denholm, Ella Reid’s “companion” and discuss how their relationship adds to my sense of queer possibility in the archives.