In this blog post, SGSAH PhD intern, Molly McCracken shares her research about the Kinecraft Society.

While we live in a world surrounded by cameras, movies, and videos, it’s easy to forget that their prominence in modern culture – and in art schools – is relatively new. Though GSA currently offers a course in Sound for the Moving Image, the artistic production of films at the School has a much longer – and lesser known – history rooting even as far back as the 1930s.

While the study of cinematic arts would remain an informal activity among students and staff in the early 20th Century, letters from GSA’s Secretary show that as early as 1931 there was interest at GSA in using films in educational settings to help train students. In correspondence, for example, they suggest films of costumed models might assist in the training of drawing, and that GSA was uniquely positioned to develop this method of teaching: “no other School of Art in Britain has the facility to carry out ideas of this kind” (GSAA/SEC/2).

In 1932, a small group of students and staff successfully lobbied to establish the Glasgow School of Art Kinecraft Society. A notice in that year’s Annual Report (GSAA/GOV/1/88) notes that the Society received a loan of £10 from the Governors to support the group’s “study and practice in the art and craft of cinema photography”, and inviting both past and present students to join. In this early stage the Kinecraft Society was engaged with making a “series of educational films suitable for showing in schools”, supporting the Director’s interest in the pedagogical value of films for GSA. However, the lack of funding and other technical difficulties did hinder a number of projects at this stage.

Around this time, the increasing prominence of both film and filmmaking at GSA inspired early debates about the merit of film as an art form. A 1933 article by J McGoldrick in Vista (GSAA/PUB/9) notes that while the Kinecraft Society was already “firmly established”, it should focus on experimental and innovative craft, rather than the simple reproduction of plays.

Certainly, the artistic and experimental potential of film was at the heart of Kinecraft’s projects in the ensuing years. The first film produced by the society was created by a group of five members: Norman McLaren, Stewart McAllister, sisters Violet and Daisy Anderson, and staff member William Maclean. Titled ‘Seven Till Five’ the production followed a day in the life at GSA; the project took several months to complete, in part because the students had to finance it without support from the School, using events such as balls and dances to fundraise their projects.

Nonetheless, the film was entered at the Scottish Amateur Film Festival (SAFF) where it was awarded a prize for Best Film. John Grierson, the adjudicator of SAFF, arranged for the filmmakers to travel to London with a grant of £2 each, where they were able to visit Pinewood Studios and the set of ‘The Thirty-Nine Steps’. In a review in The Scotsman, the film is described as “the most real piece of pure cinema” yet seen at the festival. A later article in the newspaper further celebrated the success of the Kinecraft Society in spite of its lack of funding and relative newness, stating that such a film proves art schools could produce talented “theatrical designers and cinema producers”, a field that staff had a “duty” to nurture.

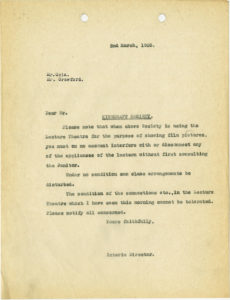

As ‘Seven Till Five’ developed a strong critical reception, letters from GSA Director James Gray suggest his encouragement of the Kinecraft Society in organising regular film screenings using School lecture theatres, and appealing to staff not to interfere with their elaborate projection set-ups (GSAA/DIR/8/2). Further correspondence held in The GSA Archives and Collections show interest in GSA’s amateur filmmakers from a number of other professional organisations and educational bodies. There are, for example, requests to screen ‘Seven Till Five’ from Grammar Schools interested in establishing their own film societies; invitations to send GSA representatives to support the formation of a Scottish National Film Council in 1934; and screenings held at GSA for the Scottish Educational Cinema Society.

After the production of ‘Seven Till Five’, GSA students Helen Biggar and Sadie McLellan became involved in the Kinecraft Society. Biggar (alongside McLaren) was involved through the production of ‘Hell Unltd’ in 1936, an experimental anti-war film that was positively reviewed and, like ‘Seven Till Five’, won an award at SAFF. The film has since been linked to the early avant-garde of British documentary filmmaking.