Skills for the Future trainee Cat looks at the impact of Belgian teaching staff at The Glasgow School of Art in the early 20th century.

Let’s start with a little context…

Before 1900, all art institutions in the UK were directed by the Government’s Department of Science and Art and aspiring tutors had to certify under this body before they could teach. This whole operation was known as the South Kensington System and was thought to encourage students to use their creative skills in industry instead of becoming fine artists.

Things changed at the turn of the century when GSA moved premises to the new Mackintosh building and student numbers began noticeably increasing. The South Kensington system ended and the school allied with the Scotch Education Department who provided annual funding and encouraged the development of a new curriculum. These factors allowed Director Francis Newbery to completely reassess the running of the school.

One of the priorities was the establishment of a more sophisticated drawing and painting department. Newbery was keen to recruit artists from elsewhere in Europe to teach on this new course in order for the school to obtain the high standards of teaching evident in the Beaux Art’s schools on the continent. He used his enthusiastic networking skills and Glasgow’s up and coming cultural status to gain the interest of artists in these countries.

Between 1901 and 1906, Newbery recruited three Belgian artists who trained at the prestigious Académie Royale des Beaux Arts. He first appointed Jean Delville and Paul Artôt, both of whom were members of the Belgian Symbolist movement.

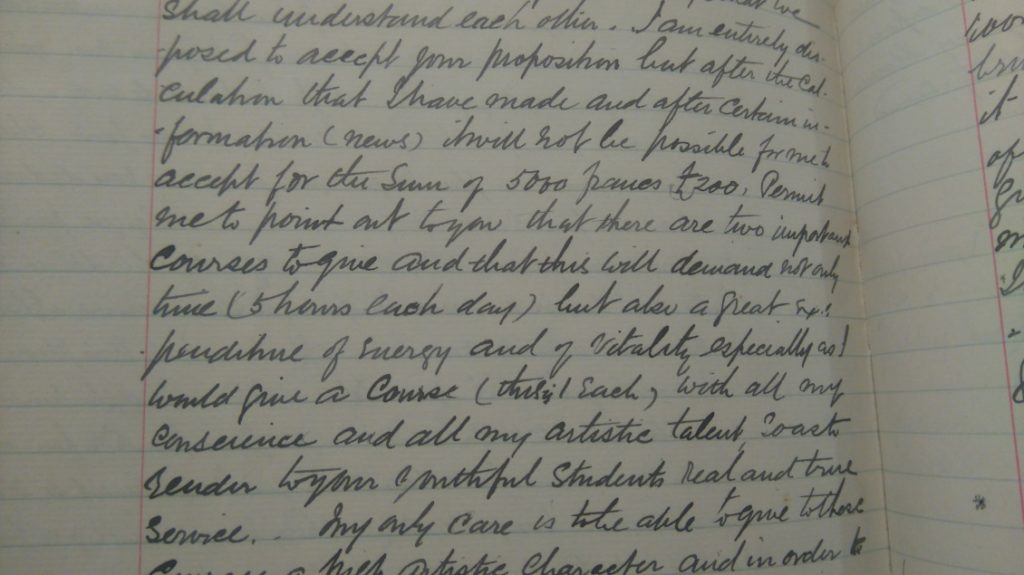

Delville was appointed Professor in charge of Life Drawing in 1901 after impressing Newbery with his work at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. As can be seen from his letter to Newbery below, he had high expectations from employment at GSA.

“It will not be possible for me to accept for the sum of £200, permit me to point out to you that there are two important courses to give and this will demand not only time but also a great expenditure of energy and of vitality, especially as I would give a course with all my conscience and all my artistic talent.”

These demands were met however and Delville remained the Professor of Life for four years. He had little knowledge of English, but Newbery believed demonstration was a much more powerful teaching tool than verbalisation. Many of his students continued in his symbolist footsteps, one even getting his work featured in renowned publication The Studio. When Delville left The Glasgow School of Art in 1905 many of his students followed him back to Belgium which is a possible indication of his influence.

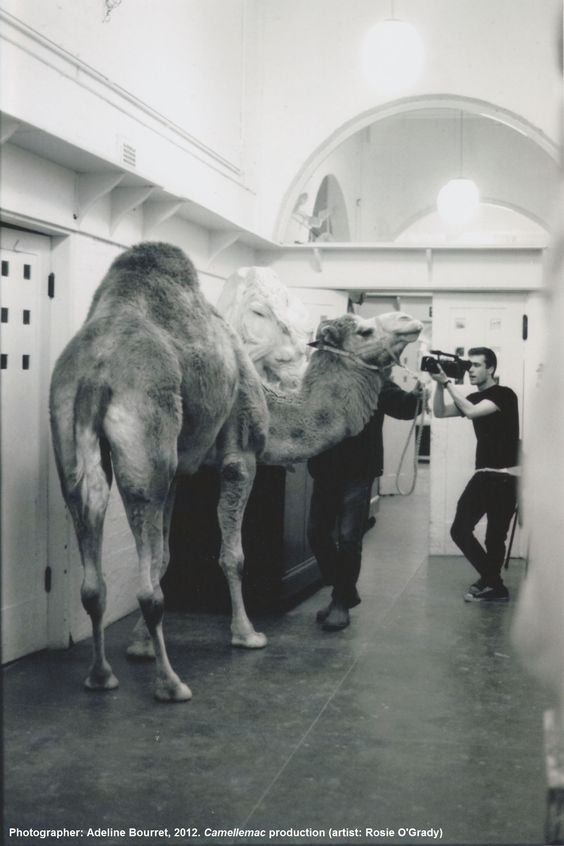

Paul Artôt was employed in 1902 and remained at the school for over ten years, progressing from professor of Life Drawing from the Antique to Head of Life and Costume Model. Possibly his most influential teaching post at the school was Life Drawing from the Living Animal. The Archives and Collections holds some amusing correspondence in relation to these classes which one former student recently used to inform her artwork!

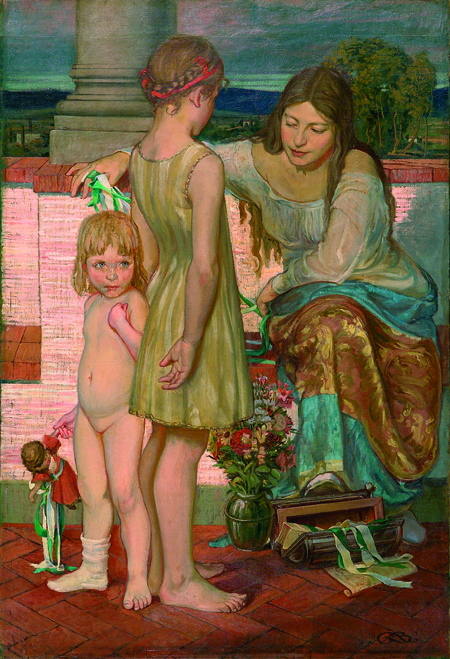

Artôt taught the students to draw in a completely different way. Heavily inspired by the Neoclassical style of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, he included a theoretical element in his classes and taught his students to draw and paint as though it were a craft.

By 1906, Newbery had recognised this importance of using theory to underpin student practice. His relationship with both Delville and Artôt drew his attention to George Baltus, another Belgian artist and lecturer. Baltus began his relationship with GSA as an occasional visiting lecturer around 1906, giving talks to the students on subjects such as composition and the history of art in major cities such as Florence. He was recruited as a permanent member of staff in 1908 and his lecture series developed to include techniques and processes. He released a book during his time at GSA called The Technics Of Painting, a copy of which can be viewed in the archives and collections search room.

Baltus returned to Belgium on the outbreak of the First World War where he stayed in active resistance to the German invasion and didn’t return to Glasgow. Some of the material held here at the archives and collections gives detail about his lectures.

Collectively, these artists had a significant influence on reshaping teaching at the school, producing more technically able students and introducing the Beaux Arts system to Glasgow.

Resources Used

The Flower and the Green Leaf: Glasgow school of Art in the time of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, edited by Ray McKenzie

The Glasgow School of Art: the history, by Hugh Ferguson

The Glasgow School of Art Archives and Collections, Records of The Glasgow School of Art, 15th century-2014

The Glasgow School of Art Archives and Collections, The Glasgow School of Art Prospectuses

Mackintosh Architecture: Context, Making and Meaning, Francis H. (‘Fra’) Newbery

Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide: a journal of nineteenth-century visual culture, The Influence of Theosophy on Belgian Artists, Between Symbolism and the Avant-Garde (1890-1910)

Sotheby’s, Paul Artot

Studio International, Visual Arts, Design and Architecture, Studio: a brief history

Tate, Académie Julian