For LGBT+ History month in February, Researcher and Archives & Collections Assistant, Helen Victoria Murray shares some of tips for researching queer people in Archives and Collections.

In Archives & Collections, we cater to a diverse audience of staff, students and the general public, many of whom are interested in queer history. We are often asked: ‘what can you tell me about the LGBTQIA+ history of GSA?’ It’s a complicated question.

It makes sense that people are eager to trace these histories within The Glasgow School of Art. We look to archives and historic collections to recognise ourselves and our communities. GSA, with its longstanding reputation for creativity and free-thinking, seems like it would be a safe haven for LGBTQIA+ people. So where are the queer folk in our archives?

Understand the Gaps

It’s important to understand the risks queer people historically faced when documenting their lives. Homosexuality was illegal in England and Wales until 1967, when the Sexual Offences Act decriminalised consenting sex between men over the age of 21. However, in Scotland, homosexuality was not decriminalised until 1980. LGBTQIA+ people were at risk of legal prosecution, discrimination and violence. As such, evidence of historical people’s sexuality or gender is not always definitive.

Traditional archival research techniques encourage us to look at sources as proof, and to avoid speculation. This is problematic in the case of queer subjects, as it can ignore important personal histories that were kept secret out of necessity. It’s still important to explore the possibilities of queerness in the archive, but our strategies might need to be more open-ended.

Look for Clues in People’s Living Circumstances

Historical research is often biased in favour of heterosexuality, and archives are no different.

For example, we can use marriage records to trace historical people’s addresses, families or professions. These documents don’t capture queer history in the same way. However, you can use other clues. If you’re researching someone you think may be LGBTQIA+, look them up in census records or registers. Do they share an address with one person over many years? Perhaps they live in a communal household with other artists?

You might have heard the phrase ‘and they were roommates’, a joke which refers to same-gender couples who live together for decades but are never openly acknowledged as queer. There are equivalent historical euphemisms, such as ‘eligible bachelors’ or ‘lady companions’ – look out for these as indicators of alternative lifestyles or queer family structures.

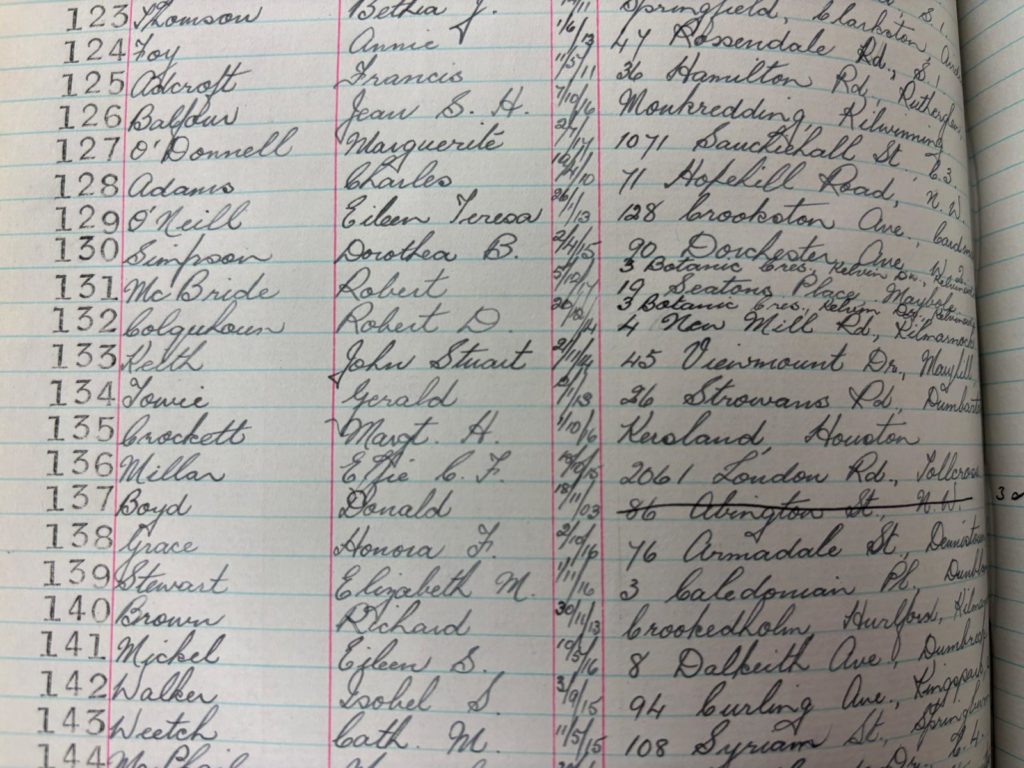

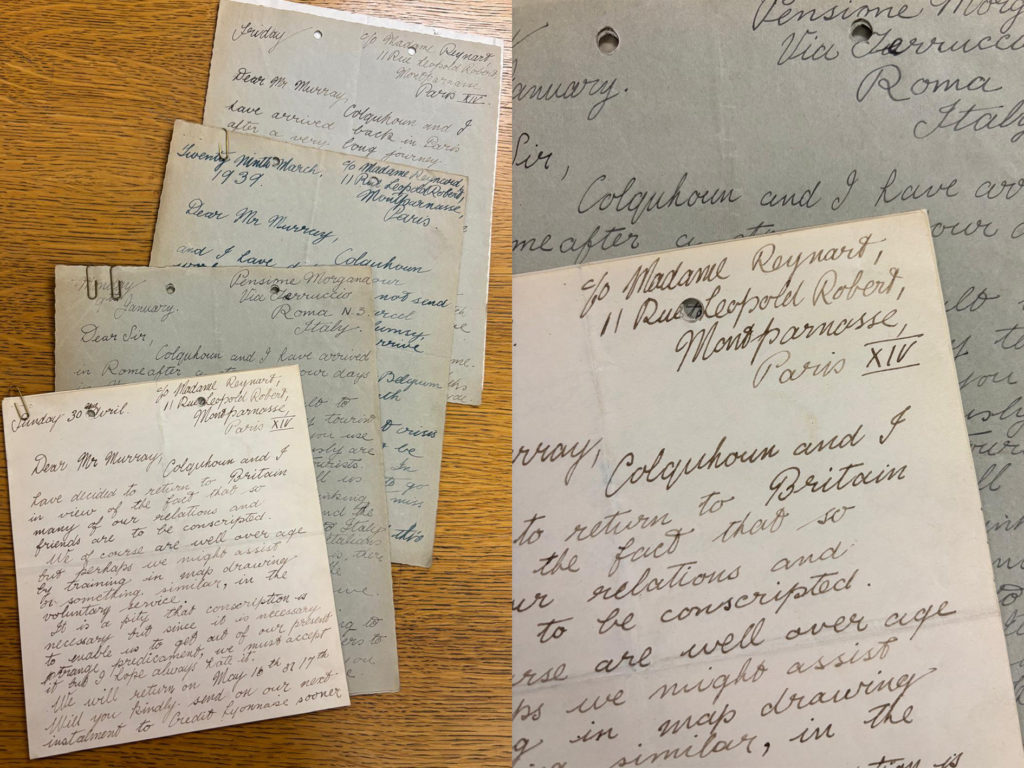

One such example from GSA Archives and Collections would be the painters Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde. The artists met at GSA in 1933 and began a partnership that was both creative and romantic. Tracing their student records, we can see that, in their first year at GSA, Colquhoun and MacBryde lived at separate addresses – but in every subsequent year, they share an address. Their registration numbers are also side-by-side, suggesting that they went together to register each new academic year.

Cross Reference

GSA Archives and Collections is an Institutional Archive – this means that a lot of the letters and papers we hold are official records. You’re unlikely to find many love letters here! But not all archives are the same. A lot of archives contain personal papers, and these can be a gold mine for exploring friendships and relationships between individuals.

If you’re researching one person in an archive, don’t just look for that individual: take note of their associates, colleagues and friends. If you widen your search, you might find more references to the person you’re looking for in other archives. Archives Hub is a really useful resource for this. It is a tool to cross-search archival descriptions throughout the UK.

Read Outside the Margins

This is one of my favourite tips for all kinds of historical research, which is to look at a source in its entirety. Let’s take a photograph, for example. Look for details – what is your subject wearing, is there anything distinctive about their self-presentation? Can you identify where the picture was taken? Has anything been intentionally removed or redacted? Flip it over for captions, descriptions and dates. These can tell you a lot about how a person identifies, or how others saw them.

Centre your own Queer Experience

Now that you know Colquhoun and MacBryde were a couple, does it change your perception of how they are portrayed? Their tutor, Ian Fleming, painted The Painters Colquhoun and MacBryde, while they were still at art school. Can you see signs of tenderness in their faces? The way their bodies point towards each other? The mirrored posture of their hands?

As queer people, we may be alert to subtle signals of queerness from people in the world around us. This can be equally true in archives. In archives, just like in the outside world, it’s important to trust those instincts.

The museum consultant Margaret Middleton has created a zine resource called Looking for Queer Possibility to help us channel gaydar into analysis. They write:

Have you ever seen something in a museum that just seems… QUEER? There’s no indication on the label and no one else in the gallery seems to be noticing what you’re noticing. But something has pinged your gaydar and caught your attention. You have found an Object of Queer Significance. Maybe you look it up on Wikipedia and confirm the object’s connection to queer history or maybe you simply found an object that speaks to you. What you see and how you feel about it is valid. Queer experience is a kind of expertise. Gaydar is a way of knowing.

When researching, try to notice what ‘pings your gaydar’ and why. Is it a person themselves? Is it how they’re dressed, or how they interact with someone else? If you’re looking at an artwork, does it remind you of a specific queer experience or emotion?

We may not definitively know how a historical person identified. After all, gender and sexuality are not always fixed categories, even within one person’s lifetime. This fact can complicate how we describe them years later.

Yet if we, as queer researchers, see echoes of ourselves in archives and collections, it is important to honour our unique perspectives. Sometimes the most important person you can find in the archive is yourself.

Some Resources for LGBTQIA+ Research in Archives

- Archives Hub https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/

- The Bi+ History Project https://bihistory.wordpress.com/

- Glasgow Women’s Library Lesbian Archive, https://womenslibrary.org.uk/explore-our-collections/the-archive-collection/the-lesbian-archive/

- Goldsmith’s Centre for Queer History https://www.gold.ac.uk/queer-history/

- It’s Radical to Exist: bisexual+ history + archiving zine https://fomapress.kit.com/products/its-radical-to-exist

- The National Archives Guide: How to Look for Records of Sexuality and Gender Identity History https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/gay-lesbian-history/

- Margaret Middleton, Looking for Queer Possibility (2022)

- Margaret Middleton, ‘Queer Possibility’, Journal of Museum Education 45:4 (2020) https://static1.squarespace.com/static/664b958ee5f0be670f887756/t/6654a978d7d0cb311aebd95a/1716824441479/Queer+Possibility.pdf

- Queer Heritage and Collections Network, https://queerhcn.org/