GU placement Hillary Fortin provides an update on her work treating and re-cataloguing our fire damaged ceramics.

As part of my work placement with the Glasgow School of Art Archives and Collections, I created a poster about a specific aspect of my placement. I decided to write about the treatment and re-cataloguing of fire-damaged ceramics which had been recovered from the Mackintosh Building after the May 2014 fire. I focused on two ceramics, a Judith Gilmour lugged pot and a Robert Stewart stoneware mug. Both objects survived the fire, but suffered notable damage.

Introduction

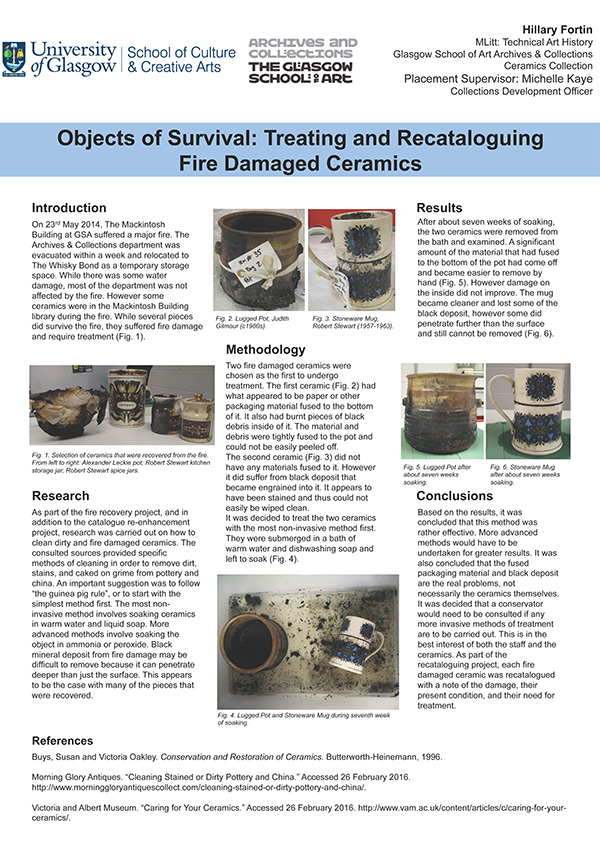

On 23rd May 2014, The Mackintosh Building at GSA suffered a major fire. The Archives & Collections department was evacuated within a week and relocated to The Whisky Bond as a temporary storage space. While there was some water damage, most of the department was not affected by the fire. However some ceramics were in the Mackintosh Building library during the fire. While several pieces did survive, they suffered fire damage and require treatment (Fig. 1).

Research

As part of the fire recovery project, and in addition to the catalogue re-enhancement project, research was carried out on how to clean dirty and fire damaged ceramics. The consulted sources provided specific methods of cleaning in order to remove dirt, stains, and caked on grime from pottery and china. An important suggestion was to follow “the guinea pig rule”, or to start with the simplest method first. The most non-invasive method involves soaking ceramic in warm water and liquid soap. More advanced methods involve soaking the object in ammonia or peroxide. Black mineral deposit from fire damage may be difficult to remove because it can penetrate deeper than just the surface. This appears to be the case with many of the pieces that were recovered.

Methodology

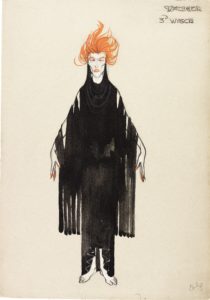

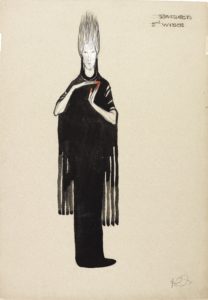

Two fire damaged ceramics were chosen as the first to undergo treatment. The first ceramic (Fig. 2) had what appeared to be paper or other packaging material fused to the bottom of it. It also had burnt pieces of black debris inside of it. The material and debris were tightly fused to the pot and could not be easily peeled off. The second ceramic (Fig. 3) did not have any materials fused to it. However it did suffer from black deposit that became engrained into it. It appears to have been stained and thus could not easily be wiped clean. It was decided to treat the two ceramics with the most non-invasive method first. They were submerged in a bath of warm water and dishwashing soap and left to soak (Fig. 4).

Results

After about seven weeks of soaking, the two ceramics were removed from the bath and examined. A significant amount of the material that had fused to the bottom of the pot had come off and became easier to remove by hand (Fig. 5). However damage on the inside did not improve. The mug became cleaner and lost some of the black deposit, however some did penetrate further than the surface and still cannot be removed (Fig. 6).

Conlusions

Based on the results, it was concluded that this method was rather effective. More advanced methods would have to be undertaken for greater results. It was also concluded that the fused packaging material and black deposit are the real problems, not necessarily the ceramics themselves and it was decided that a conservator would need to be consulted if any more invasive methods of treatment are to be carried out. This is in the best interest of both the staff and the ceramics. As part of the re-cataloguing project, each fire damaged ceramic was re-catalogued with a note of the damage, their present condition, and their need for treatment.

Resources Used

Conservation and Restoration of Ceramics, by Susan Buys and Victoria Oakley, 1996.

Morning Glory Antiques, Cleaning Stained or Dirty Pottery and China

Victoria and Albert Museum, Caring for your Ceramics