Mackintosh Art, Design and Architecture Collection

- MC

- Collection

- c1891-2018

Items in The Glasgow School of Art's Mackintosh collection include: furniture, watercolours, drawings, architectural drawings, design drawings, sketchbooks, metalwork and photographs.

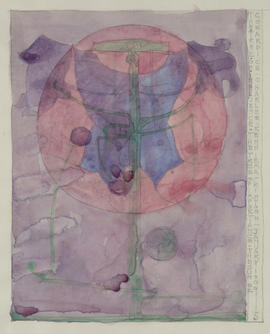

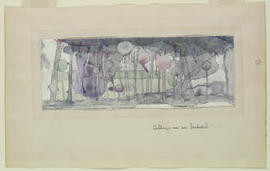

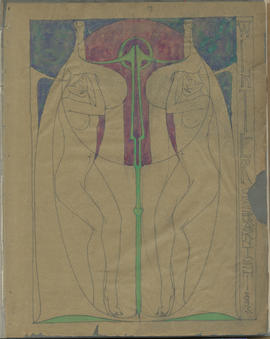

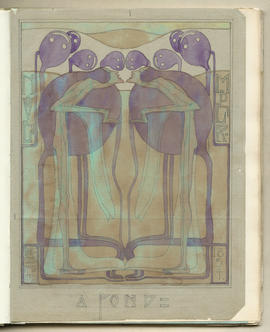

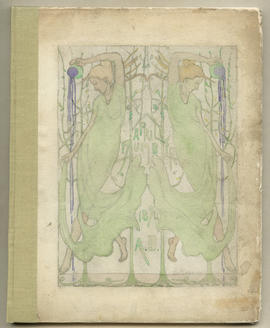

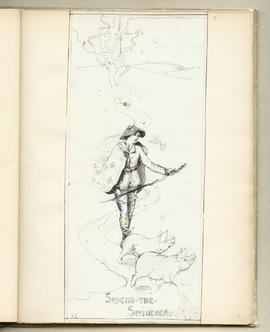

Mackintosh studied evening classes at the Glasgow School of Art between 1883-1894, winning numerous student prizes and competitions including the prestigious Alexander Thomson Travelling Studentship in 1890. Mackintosh and his contemporaries also produced four volumes of a publication called "The Magazine" during their time as students, which included examples of their writing and artworks. GSA Archives and Collections hold Mackintosh's Italian Sketchbook, as well as all four volumes of The Magazine, all of which can be browsed on our catalogue.

The majority of Mackintosh's three-dimensional work was created with the help of a small number of patrons within a short period of intense activity between 1896 and 1910. Francis Newbery was headmaster of The Glasgow School of Art during this time and was supportive of Mackintosh's ultimately successful bid to design a new art school building in 1896 - his most prestigious undertaking. For Miss Kate Cranston he designed a series of Glasgow tearoom interiors and for the businessmen William Davidson and Walter Blackie, he was commissioned to design large private houses, 'Windyhill' in Kilmacolm and 'The Hill House' in Helensburgh. In Europe, the originality of Mackintosh's style was quickly appreciated and in 1900 he was invited to participate at the 8th Vienna Secession.

In 1902 Mackintosh was invited to participate at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art in Turin and later at exhibitions in Moscow and Berlin. Despite this success Mackintosh's work met with considerable indifference at home. Few private clients were sufficiently sympathetic to want his 'total design' of house and interior and he was incapable of compromise.

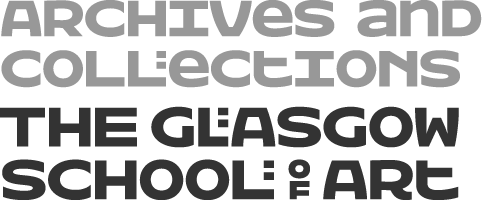

By 1914 Mackintosh had despaired of ever receiving true recognition in Glasgow and together with his wife Margaret Macdonald he moved, temporarily, to Walberswick on the Suffolk Coastline (in England), where he painted many fine flower studies in watercolour. In 1915 the Mackintoshes settled in London and for the next few years Mackintosh attempted to resume practice as an architect and designer. The designs he produced at this time for textiles, for the 'Dug-out' Tea Room in Glasgow and the dramatic interiors for 78 Derngate in Northampton, England show him working in a bold new style of decoration, using primary colours and geometric motifs.

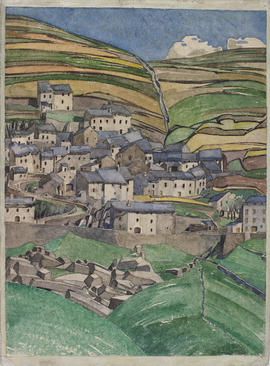

In 1923 the Mackintoshes left London for the South of France, finally living in Port Vendres where Mackintosh gave up all thoughts of architecture and design and devoted himself entirely to painting landscapes. He died in London, of cancer, on 10 December 1928.

The majority of Mackintosh's design work, (including furniture and metalwork), architectural drawings, textile designs and watercolours are in the possession of three public collections - The Glasgow School of Art, Glasgow Museums, and the Hunterian Art Gallery at the University of Glasgow - although significant (individual) pieces can be found in museums across the UK and Europe, North America and Japan. However, some of Mackintosh's most important, symbolist watercolours from the early to mid-1890s are to be found in the collection of The Glasgow School of Art.

The Glasgow School of Art Archives and Collections hold a large number of items by Mackintosh, giving us one of the largest collections of his work held in public ownership. The collection is one of 50 Recognised Collections of National Significance to Scotland. We continue to investigate new routes of engagement for the collection. For example, our Mac(k)cessibility project in conjunction with GSA’s School of Simulation and Visualisation explores digital display and loans of our Mackintosh furniture. Find out more about the Mac(k)cessibility project here.

Mackintosh, Charles Rennie