Continuing to look into the impact of continental staff in the early 20th century, Skills for the Future trainee Cat Doyle investigates eminent sculptor Johan Keller’s time at GSA.

Sculpture was taken very seriously at GSA in the late 19th century. It was believed that studying it would benefit every artistic discipline and a significant proportion of the School’s budget was spent on acquiring plaster casts for the students to draw from.

William Kellock Brown resigned as the director of GSA’s sculpture department – or modelling department as it was then known – in 1897, feeling that his teaching duties were overshadowing his own creative practice. Brown was succeeded in 1898 by Dutch artisan Johan Keller.

Originally from The Hague and previously working in Paris as a wax work model maker, it is unclear whether Keller moved to Glasgow specifically to take up this post or had simply arrived in the right city at the right time. He is recorded in the 1901 census as living with his wife in Glasgow aged 37. Regardless of what brought him here, he certainly fitted with director Francis Newbery’s new continental approach for the School at the turn of the 20th century.

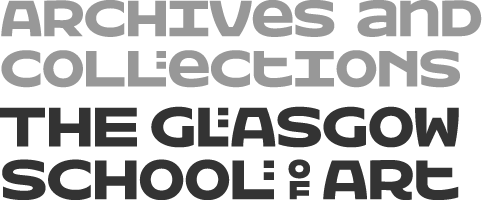

It is evident from photographs during this period that Keller taught a very skills-based approach to sculpture. Each of his students created identical work, mastering their craft through technique. Modelling was possibly taught in this way because many students were also employed labourers and were taking classes at GSA to improve their hand skills.

This is a complete contrast to the practice of sculpture today which is commonly lead by the unique creativity of the individual. Glasgow Sculpture Studios current exhibition You be Frank, and I’ll be Earnest is a fantastic example of modern sculpture practice.

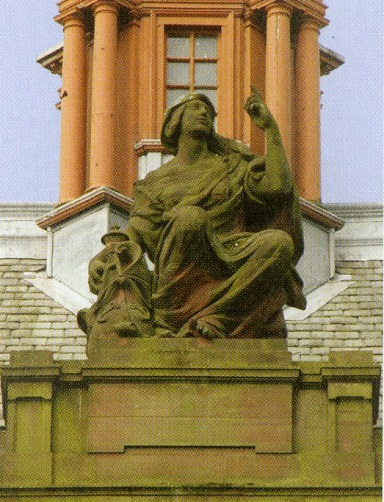

Alongside his teaching post, Keller managed to commission a large number of his own works and take part in several exhibitions. He exhibited multiple times as part of the Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture’s annual exhibition as well as with the Royal Glasgow Institute of The Fine Arts. He was also the only artist in Glasgow who contributed to the series of sculptures produced for the new Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum as part of the Glasgow International Exhibition in 1901.

Unfortunately however, Johan Keller did not meet all of director Francis Newbery’s expectations during his time at the school. His level of competence continually fluctuated and he was found asleep during an inspection by renowned sculptor James Pittendrigh MacGillivray in 1904. Student numbers in the modelling department declined shortly afterward, which Keller put down to the fact that “sculpture is not as popular in Glasgow”.

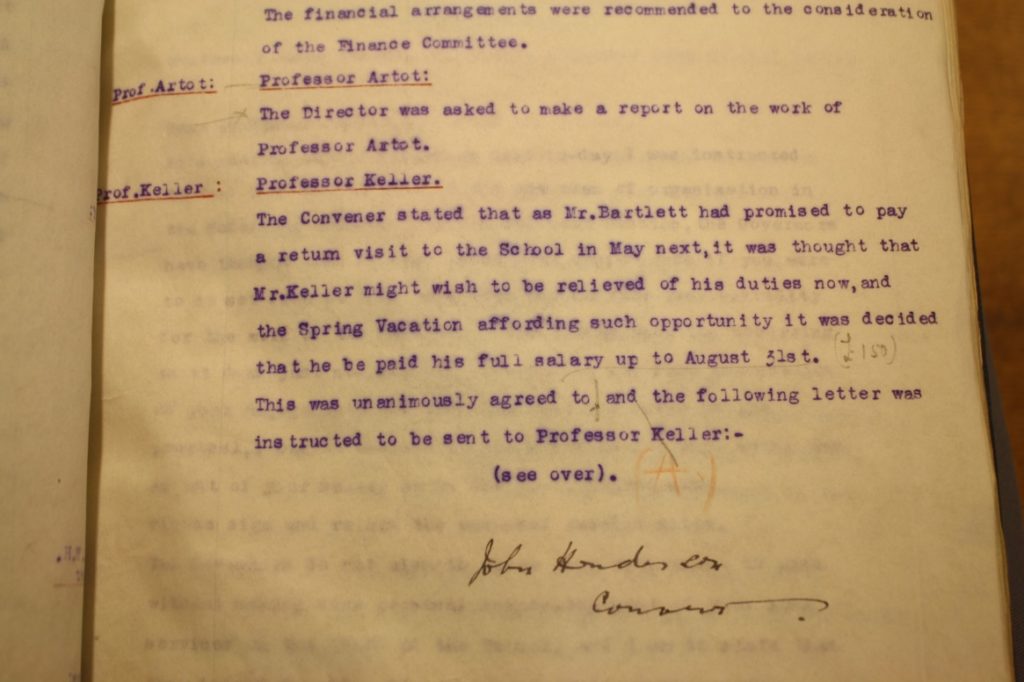

Keller resigned in February 1913 to take effect later in the year. However he was dismissed early by the school’s governors who offered to pay him his full salary if he left before the end of the academic year. It is possible that he may have continued his post if he had devoted more time to running the department and less to his own commissions.

The story of Johan Keller’s time at the School highlights the fact that Newbery’s employment of international staff didn’t always have a positive influence. Paul Artôt, who we met in a previous blog post, let his standards get increasingly lax as time went on and a bitter relationship developed between himself and Newbery. He too was forced to resign by GSA’s governors in 1913 when he was beginning to establish himself as an artist in his own right.

Throughout the governor’s minutes from this period, there are frequent references to requests for pay increases from international staff. It is interesting to consider whether Keller and Artôt’s complacency was caused by feelings of unfair employment or that they simply regarded themselves more highly as artists.

Resources Used

The Flower and the Green Leaf: Glasgow school of Art in the time of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, edited by Ray McKenzie

Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain & Ireland 1851-1951, Johan Keller