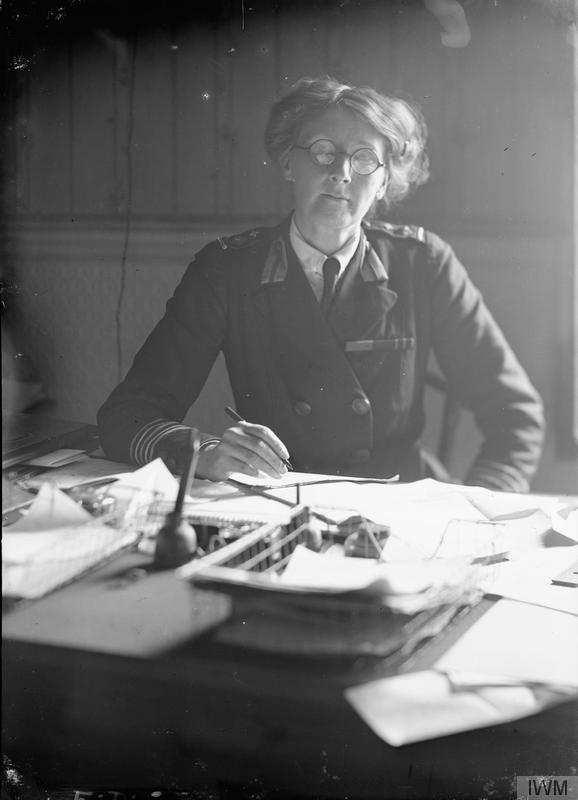

Continuing our research into individuals associated with the GSA during the First World War (find out more about the current exhibition of archive materials from this period in ‘From the service of Venus to the worship of Mars’) Maja Shand continues with her research into the entrants on the GSA Roll of Honour, and reveals the fascinating story of Dr Tina Gray.

In one of my previous posts, I told the story of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, of which Glasgow Girl Norah Neilson Gray was a member. In this post I will explore the pivotal work of trained and untrained nurses during the First World War, and in doing so hope to provide a context to the work of Norah’s sister and Role of Honour entrant, Tina Gray, who volunteered as a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse in France.

Although playing an important role in the history of women’s advancement in the medical professions, the Scottish Women’s Hospitals were very much an exception to the rule. The majority of women who worked in medical roles during the First World War were either trained nurses or VADs (Voluntary Aid Detachments), women from predominantly wealthy families who put themselves forward as medical volunteers to the British Red Cross. For these women, working for the British Red Cross was primarily a means to exercise their patriotism, which they did with gusto. As historian Janet S K Watson expresses, the hospital wards were their ‘metaphorical battlegrounds’. A language of militarism slowly seeped into the VADs’ everyday discourse, helped along by the quasi-military structure of many hospitals. Voluntary nursing became women’s equivalent of active service.

Trained nurses, on the contrary, fought a very different war. They tended to be from middle class families who lacked the financial means to support unmarried daughters. Historically, nurses had been regarded as somewhat of a threat to the male medical establishment, although, unlike that of women doctors, their work was at least in line with what was considered to be their biologically determined duty as caregivers. In contrast to the VADs, their struggle was for professional recognition, to be enshrined in the state register of nurses – for which a bill was first put forward in 1905. It is said that trained nurses resented the entitlement of the VADs, who in spite of having very little training, became automatically referred to as nurses and sisters by hospital interns. This hierarchical struggle became particularly amplified in territorial hospitals. According to Watson, many VADs hoped to be posted to military hospitals in France, where overburdened hospitals meant that VADs were given more responsibilities, and military nurses – often of higher social standing – did not feel the need to reinforce their authority.

Women doctors, as I mentioned in my previous post, weren’t allowed to work on the front, and were denied the status and commissions given to members of the Royal Army Medical Corps – although they could still be found working in War Office sanctioned military hospitals. According to historian Janet S K Watson, even the Royal Army Medical Corps officers weren’t considered ‘real’ officers by those in combat, or those working on the Front. The RAMC, having been founded in 1898, was itself a relatively new arm of the military, and there was said to be a historic distrust of doctors in the British Army.

So what were the repercussions of these advancements for medical women after the war? Nurses saw the passing of the Bill of Registration in 1919, which meant that all who had undergone the necessary three years’ training would be given the professional recognition that they deserved.

Sadly, women doctors did not achieve quite the same recognition. It was to take another 30 years and another global conflict until women doctors were finally granted military commissions. Winston Churchill, in response to a petition by Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson, denied commissioning to women doctors by congratulating women’s ‘exceptional’ work for the duration of the war – but an exception it was to remain. Despite having seen a rise from 10 to 40 percent enrolment of women in medical schools, these figures shrunk again after the war. Only 557 Red Cross Society scholarships awarded were awarded to former VADs – the majority of which were used towards midwifery and nursing training. Only 13 of these were used by women to go to medical school.

One of these thirteen women was Glasgow School of Art graduate Tina Gray. Look out for my next post, where I will tell her remarkable story.

Resources Used

University of Glasgow, The University of Glasgow Story: Tina Gray

Fighting Different Wars: Experience, Memory and the First World War in Britain, by Janet S. K. Watson – p268

War in the Wards: the Social Construction of Medical Work in First World War Britain, by Janet S. K. Watson, Journal of British Studies 41 (October 2002) – p484-510

British Medical Journal Obituary, Vol 289 22nd September 1984 p773

Miss Tina Gray, British Red Cross VAD Cards