Our Skills for the Future Trainee, Maja Shand continues with her research into the First World War and traces some of our GSA Alumni to Canada.

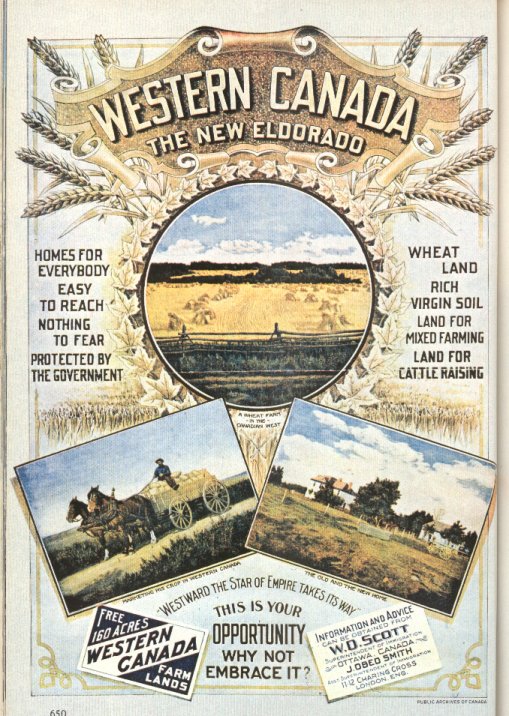

Two years after Canada was founded in 1867, the country’s newly formed government introduced an immigration policy that was designed to encourage Northern Europeans – particularly those with agricultural backgrounds – to populate and cultivate the land of its Western territories, made accessible after the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Entry to Canada was limited to those who could fulfil regulations introduced to restrict the diversification of Canadian society – thus ethnic minorities, disabled or poor Europeans were often turned away. The country’s indigenous population, too, were displaced from their land in order to make way for the white European agrarian settlers who poured in from Eastern Canada. With the north-western bison practically wiped out by the Hudson Bay Company’s profit-driven hunting campaign, the First Nation peoples either starved or accepted the government’s devastating programme of assimilation.

After an aggressive recruitment campaign in Britain, a wave of passable Scottish migrants headed to the eastern shores of Canada with the promise of prosperity, professional advancement, and a better quality of life.

These included a number of GSA graduates, nine of whom appeared on the Roll of Honour. The majority of these alumni were architects, and some artists, for whom Canada would soon become a tabula rasa on which to project their professional and artistic ideals. Artist Charles H Scott, a founding member of British Columbian Arts League, lobbied for the establishment of an art school and gallery in Vancouver, and later became principal of Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Art (Vancouver School of Art) until 1952, as well as being instrumental in the acquisition of Vancouver Art Gallery’s permanent collection.

Similarly, Alexander Johnstone Musgrove established the Winnipeg School of Art at which he later taught, as well as the city’s first public art gallery which he directed.

Among GSA’s newly qualified architects were Tom Pomphrey, whose most notable design was the art deco Toronto water filtration plant on the shores of Lake Ontario. Similar was James M Stevenson – resident architect for the federal department of public works, Alberta, who later went into partnership with his son in firm that was to become one of the largest architectural offices in Western Canada.

Lesser known were architects David McAusland Carlile, William Ferguson, and Robert Harvie, who worked as a civil engineer in Vancouver and died in combat on Aug 31st 1918. Artists David Hill and John Chisholm MacHutcheon – who during the war served in the Canadian Cyclist Battalion and Sherwood Forresters, falling at Gallipoli on 2nd August 1916 – were also among them.

What brought these men together, apart from their participation in one of the 19th and 20th centuries’ most significant settlement programmes, is the event that spelled the beginning of the end of the empire that violently and irrevocably changed the ethnic and cultural make-up of the northern Americas.

The First World War seemed invariably to stir an unquestionable sense of patriotism in Canada’s recent European immigrants, and years before conscription was introduced (in August 1917, more than a year after Britain) men rushed to join the Canadian Expeditionary Forces. Among them were our nine GSA alumni, several of whom would not return, but most of whom miraculously found their way back.

Unlike their British comrades, whose military records were destroyed when a government building was bombed during the Second World War, many of the attestation papers of these men have been digitised, and can be found on the Canadian Government’s database of soldiers of the First World War. These provide revealing details such as place of attestation and origin, next of kin, and even physical description, and are an invaluable resource for researchers and historians.

To read more about the individuals who served in the Canadian Expeditionary Forces, see their biographies on our catalogue here.

Resources Used

focus MIGRATION, Canada

Canadian War Museum, Canada at War

British Immigrants in Montreal, Canadian Immigration – Early 1900s

Biographical Dictionary of ARCHITECTS IN CANADA 1800-1950, Introduction

Canadian Heritage Information Network, Artist/Maker Name “Musgrove, Alex J. (Alexander Johnston)

Library and Archives Canada, Service Files of the First World War, 1914-1918

Vancouver Art Gallery, Charles Hepburn Scott, Alfresco, 1923